SCERTS & Emotional Regulation: What’s the End Game?

Everyone who supports autistic individuals is talking about emotional regulation, the “ER” of the SCERTS model. But what is emotional regulation and why is everyone so focused on it? And how does it fit within the bigger picture of providing appropriate, efficacious, and person-centered educational support for autistic individuals?

What Is Emotional Regulation?

Emotional regulation is a developmental process that evolves and matures across the lifespan. It is the capacity to shift one’s internal emotional state and state of arousal (energy level, for example) to meet demands or match the characteristics of one’s social and physical environment. This means it forms the foundation of a person’s ability to engage in daily activities.1

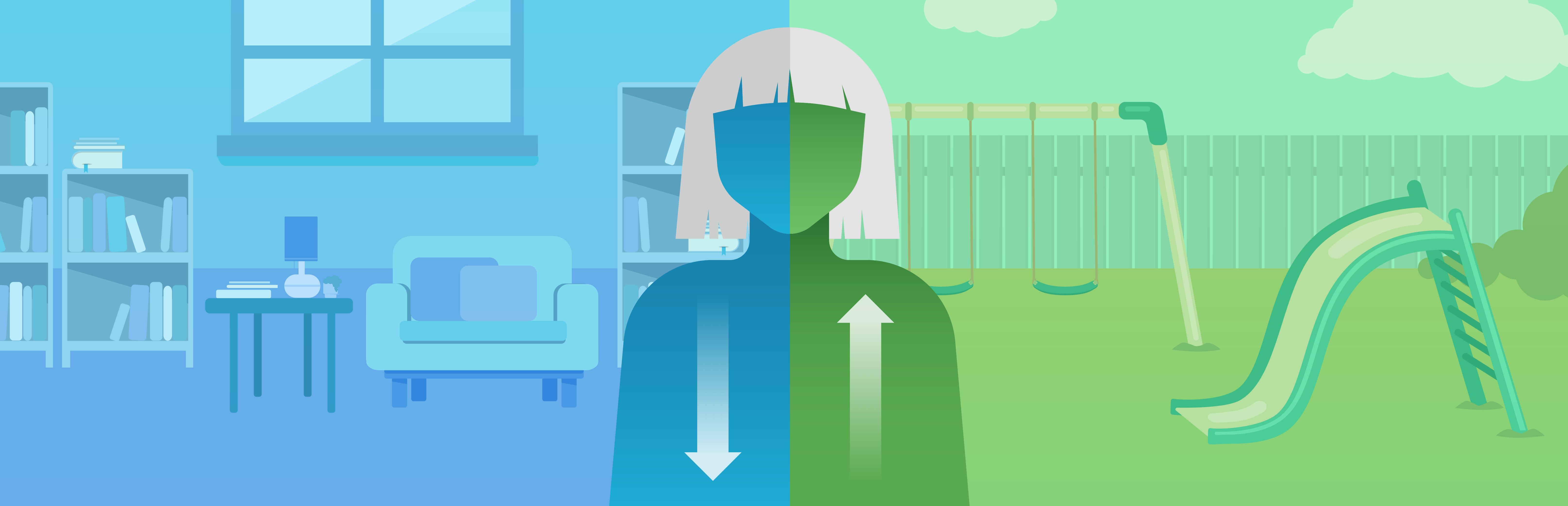

Think of it this way: When someone is “well-regulated,” their internal energy/arousal state is a good match for the environment and what they are doing in that environment. For example, a high energy and positive emotion state is a good match for playing at recess or running around in a physical education class. On the other hand, a calm energy and arousal state is a good match for quietly reading in the library.

Matches between individual arousal states and the energy requirements of activities and environments underlie successful participation in virtually all activities and interactions. When there is a mismatch between the person’s state and their environment, we often refer to the resulting experience and observable behavior as dysregulation.

To achieve or come closer to matching our arousal level with the energy necessary for a particular environment—or to maintain our current arousal state—we use our emotional regulation skills.

What Are Emotional Regulation Skills?

There are two distinct types of emotional regulation skills:

- Self-regulation skills, which we have at our own disposal and use independently to help shift our energy state and emotional intensity

- Mutual-regulation skills, which we can use to access or respond to the help of others for shifting our energy state and emotional intensity

Self-regulation and mutual-regulation skills include a range of strategies and vary depending on the individual’s developmental level. In general, they can be divided into three different categories:

- Sensory motor/behavioral—Strategies that provide or remove sensory input and movement

- Language-based—Strategies that give information and often support routine

- Metacognitive—Strategies that focus on reflective and forward thinking

Why Is Emotional Regulation a Challenge for Autistic Individuals?

Autistic individuals often struggle with communication and social learning differences, which can contribute to social anxiety and the delayed acquisition of emotional regulation skills. Autistic individuals also frequently have underlying sensory processing challenges and coexisting physiological conditions, such as sleep disorders or allergies.

Each of these differences can be considered a risk factor that predisposes the autistic individual to emotional dysregulation and energy mismatches. The unique neurology and learning styles of autistic individuals contribute to their frequent dysregulation experiences, which further impact an individual’s opportunities and abilities to interact with others, participate in daily activities, and learn in structured settings. Sometimes the outcomes of these difficulties present as challenging or even dangerous behaviors, such as impulsivity, difficulty accepting challenges in routines, or self-injury.

How Does the SCERTS Model Help Provide the Needed Support for Emotional Regulation?

In many traditional approaches, the end game winds up being the elimination of challenging behaviors and the use of compliance training to “support” difficulties engaging. This translates into goals that focus on “calm and quiet.”

Alternatively, the SCERTS model is designed to help educational teams understand the experience of the autistic individual and determine where supports are needed to scaffold the development of emotional regulation skills. These skills, in turn, lessen or prevent energy mismatches and emotional dysregulation, which is what often results in more challenging behavior. This approach, rather than focusing on the behaviors themselves, forms the foundation for supporting the model’s overarching goals:

- Bolstering active engagement for autistic individuals

- Developing supportive and meaningful relationships

Both of these goals have been highlighted as key elements in efficacious interventions.

Within the SCERTS model, the focus centers on developing new self-regulation and mutual-regulation skills to support a person’s availability for learning and interacting in a variety of activities and environments. It also equips them with more tools to navigate transitions, delay gratification, and cope with everyday stresses. As the autistic individual’s regulation tools expand and diversify, problem behaviors often naturally decrease.

Because the SCERTS model provides a framework for partners that prioritizes the teaching of emotional regulation strategies to help bring energy closer to levels that support engagement, the nature of the skills targeted will depend on the developmental level of the individual. Examples may include partners teaching:

- Sensorimotor strategies, such as running to increase arousal or chewing gum to decrease arousal

- Language-based strategies, such as using a schedule to navigate their day or words to convey their emotional state to partners

- Systems for reflecting on the utility of self-regulation and mutual-regulation strategies and for planning their use in the future

At times, targeted emotional regulation skills may help an individual attain and maintain a calm state to match a low-key activity in a quiet environment—but this is only one of many emotional regulation priorities.

Jacquelyn Fede, PhD, an autistic individual, explains:

“By the time I am in a meltdown or a shutdown, it is too late. Focusing on these resulting behaviors, in which I don’t want to engage either, is not helpful to me in any way. They are not voluntary; there are no thought processes that put them in motion or are capable of controlling them. They are the product of energy that has built to the point of eruption. Through SCERTS, I have learned to identify different states and recognize matches and mismatches for my daily tasks. I have been armed with strategies to move my own energy up or down closer to the energy needed. I have been empowered with understanding and the tools to act rather than scrutinized for outcomes over which I had no control.”

Emotional regulation skills are necessary for helping individuals move toward a variety of energy levels appropriate for all types of activities and environments. When an individual has the skills to navigate these needed transitions, it fosters a sense of competence, emotional well-being, and positive self-esteem.

- Cole, P. M., Martin, S. E., & Dennis, T. A. (2004). Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development, 75(2), 317–33.

- Prizant, B. M., Wetherby, A. M., Rubin, E., Laurent, A. C., & Rydell, P. J. (2006). The SCERTS Model: A Comprehensive Educational Approach for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Volume I: Assessment. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Prizant, B. M. Wetherby, A. M., Rubin, E., Laurent, A. C., & Rydell, P. J. (2006). The SCERTS Model: A Comprehensive Educational Approach for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Volume II: Program Planning and Intervention. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Autism Level UP! www.amy-laurent.com