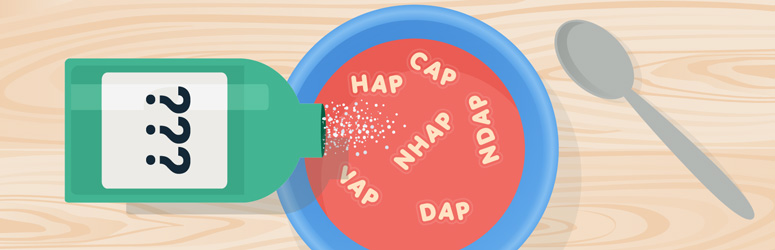

Pneumonia Alphabet Soup (Part 2): The Secret Ingredients

We began deciphering the recipe for pneumonia in Part 1 – Pneumonia Alphabet Soup: Reworking the Recipes

Causes for pneumonia are multifactorial, and the clinician needs to consider the following factors:

- Pneumonia risk factors (like dependency on others to perform oral care)

- Patient’s functional baseline status before getting sick

- Events leading up to the onset of the acute illness

Taking a holistic approach to diagnosis and treatment helps the medical team see all the potential ingredients of the “pneumonia soup.” If aspiration pneumonia caused by several different factors is suspected, there is still work to be done to uncover the secret ingredients.

Ask More Questions

Was it a sudden onset within acute care?

Pneumonia acquired in acute care may be caused by a sudden aspiration event, dysphagia, or an iatrogenic cause (An unintended adverse complication or side effect of medications, treatment, or invasive procedures, like intubation.).

In a 1998 study, Langmore and colleagues separately analyzed acute care subjects to determine their specific factors associated with pneumonia. While the number of decayed teeth and dependence on oral care continued to play a significant role, the study also found that dysphagia and aspiration were strongly associated with pneumonia.1 Specifically, the following are pneumonia risk factors associated with dysphagia and aspiration:

- Aspiration of food

- Pharyngeal delay

- Premature spillage to the pyriform sinuses

- Excess residue post-swallow

Patients at risk for aspiration have higher rates of 1-year mortality, readmissions, recurrence of pneumonia, and development of gram-negative bacteria.2 The following factors place patients in an aspiration risk group:3,4

- Witnessed aspiration

- Vomiting

- Dysphagia confirmed by formal evaluation

- Impaired consciousness from ETOH/drugs/medications

- Chronic neurologic diseases and disorders

- Esophageal disorders and obstructions

The hospitalized patient, when conditions are ripe, has an elevated risk for a nosocomial infection like Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP). This risk could potentially be minimized by establishing a hospital-wide screening protocol, and evaluation by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) upon failing the screen.

Was it a gradual onset?

With our elderly patients from nursing facilities, we often say, “That was the straw that broke the camel’s back.” In other words, the resident may have followed a more gradual functional decline due to chronic disease, bedridden status, and dependency, leading to increased severity and frequency of aspirations along with the eventual inability to compensate.5 This patient may be admitted to the hospital with what used to be labeled as a Nursing-Home Acquired Pneumonia (NHAP) and now is termed HealthCare-Associated Pneumonia (HCAP).

Which came first: aspiration, dysphagia or pneumonia?

To sort this out, I think the most useful labels I have seen were presented by Dr James Coyle, PhD, CCC-SLP, BCS-S and Christine Matthews, CScD, CCC-SLP, of the University of Pittsburgh:6,7

- Dysphagia-Related Aspiration Pneumonia (DAP)

- Non-Dysphagia-Related Aspiration Pneumonia (NDAP)

To select the appropriate label, we need to figure out if the functional decline and the aspiration pneumonia were due to a pre-existing dysphagia or not. Coyle and Matthews used the, “chicken or the egg,” analogy with this question:

“Is the clinician seeing the chicken (dysphagia caused the aspiration pneumonia) or the egg (pneumonia has caused acute reversible dysphagia)? It is possible that the truth is more complex—that dysphagia has caused pneumonia that has acutely worsened pre-existing dysphagia.” 8

To break down that complexity, let’s address each potential secret ingredient individually.

Analyzing the Ingredients

1. Did dysphagia come first?

If so, we would use the label Dysphagia-Related Aspiration Pneumonia (DAP). However, this label does not tell the whole story.

a. What type of dysphagia?

Was it an oral dysphagia, an oropharyngeal dysphagia, an esophageal dysphagia, or all of the above? Pharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia frequently co-occur. Langmore’s team found esophageal dysmotility to be significantly associated with pneumonia, potentially due to slow and incomplete esophageal emptying.9 Esophageal disorders and obstructions placed patients in the aspiration-risk group in Taylor’s study.10 Backflow or retrograde flow of food/liquid – due to esophageal dysphagia – can enter the airway (aka laryngopharyngeal reflux/LPR, pharyngoesophageal reflux, or supraesophageal reflux and aspiration).

As stated in my previous MedBridge blogs, Good Evaluations Guide Treatment: What Are We Doing Wrong?, and Good Evaluations Guide (Part 2): The Clinical Examination and Scope of Practice, instrumental testing is the best way to assess the pathophysiology of the swallow. After testing, the clinician can make appropriate referrals if esophageal issues are suspected.

b. When did the dysphagia start?

Was it an acute or gradual onset of dysphagia? This may take careful research during your clinical evaluation. Keep in mind, what gets labeled as a Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) may be due to chronic dysphagia. If no chronic baseline of dysphagia exists, that brings us to our next question.

2. Did a functional decline from an infection come first?

Upper respiratory infections or urinary tract infections can cause generalized weakness, fever, lethargy, delirium, and a new bedfast state. Confusion is caused by the acute infection and can be exacerbated by medications and an unfamiliar environment with an interrupted sleep schedule. The weakness and cognitive changes can contribute to swallowing difficulties, leading to increased aspiration risk. This should be cautiously labeled a Dysphagia-Related Aspiration Pneumonia (DAP).

It’s important to remember the absence of baseline dysphagia. Maybe the person’s baseline was independent and high functioning. Once a person is labeled, “a dysphagic aspirator,” the label may stick for too long. The medical team may feel pressure to be overly restrictive. Clinicians must assess whether aspiration and dysphagia were due to decompensation and not related to any underlying pathology of the swallowing musculature. The goal should be to quickly upgrade the patient’s diet once the acute phase has resolved.

3. Did a vomiting and/or refluxing episode come first?

Aspiration pneumonitis due to vomiting is an example of a Non-Dysphagia Related Aspiration Pneumonia (NDAP).11

Distinctions need to be made between aspiration pneumonia and pneumonitis. The former is caused by aspiration of material colonized by pathogens, from the oral cavity or GI tract in the presence of proton pump inhibitors. The latter is a non-infectious chemical burn or lung injury causing inflammation. However, an acute inflammation can make the lung more susceptible to a subsequent infection. Aspiration pneumonitis may be overlooked, causing patients to potentially be over treated with antibiotics.

That said, similarities can be found between aspiration pneumonia and aspiration pneumonitis, especially in prevention, “For both syndromes, the best strategy is prevention. Preventive measures in the preoperative period and in the chronically ill patient at high risk for aspiration must be ensured to avoid complications.”12

4. Did the pneumonia come first?

Pneumonia may be caused by aspiration of colonized oral pathogens along an endotracheal tube (Ventilator Acquired Pneumonia). This can be considered a Non-Dysphagia-Related Aspiration Pneumonia (NDAP).

Another example is how a severe septic state (i.e., urosepsis) can progress into a hematogenous pneumonia. This type of pneumonia should not be labeled a Non-Dysphagia-Related Aspiration Pneumonia, as it is NOT an aspiration pneumonia.

It is our job to recognize that the subsequent lethargy, weakness, medication side-effects, and intubations can cause an acute reversible dysphagia. If we recognize the risks and recommend proceeding with caution, we can minimize the risk for an additional nosocomial-multifactorial aspiration pneumonia. Once the acuity is resolved, we can advocate for re-evaluations, especially at the rehabilitation center. Again, the goal should be to return the patient to oral intake with the least restrictive diet as soon as possible.

Understanding the Secret Ingredient

The letters in the pneumonia soup float on the surface but don’t necessarily point to a root cause. We need to dig in deeper, stirring and tasting the soup to find the secret ingredients.

We need to evaluate the patient’s current cognitive, oral motor, speech-language, voice and swallowing status. We also need to critically analyze the patient’s baseline functional status, past medical history, onset of current illness, and related factors that can contribute to an increased risk of dysphagia, aspiration, and/or pneumonia. We should ask questions to better understand the context surrounding the patient’s acute condition. It’s important to be careful with our assessments and recommendations though. If we emphasize the severity of the dysphagia and aspiration risk in our documentation, then the medical team may be quick to jump to NPO status and a feeding tube without considering the bigger picture.

My husband can take a spoonful of soup and guess the secret ingredients, declaring, “Ah, lemon and cardamom.” The medical team looks to the SLP to help understand the special recipe that went into the patient’s pneumonia.

- Langmore, S.E, et al. (1998). Predictors of aspiration pneumonia: How important is dysphagia? Dysphagia, 13, 69-81.

- Taylor, J.K., Fleming, G.B., Singanayagam, A., Hill, A.T. & Chalmers, J.D. (2013). Risk factors for aspiration in community-acquired pneumonia: Analysis of a hospitalized UK cohort. The American Journal of Medicine, 126 (11), 995-1001.

- Chalmers, J.D., Taylor, J.K., Singanayagam, A., Fleming, G.B., Akram, A.R., Mandal, P., et al., (2011). Epidemiology, Antibiotic Therapy, and Clinical outcomes in Health Care-Associated Pneumonia: A UK cohort study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 53 (2), 107-113. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir274 https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/53/2/107/285093

- Taylor, J.K., Fleming, G.B., Singanayagam, A., Hill, A.T. & Chalmers, J.D. (2013).

- Langmore, S.E, et al. (2002). Predictors of aspiration pneumonia in nursing home residents. Dysphagia, 17 (4), 298-307.

- Coyle, J.L. & Matthews, C. (2010). A dilemma in dysphagia management: Is aspiration pneumonia the chicken or the egg? The ASHA Leader, 15, 14-17. doi:10.1044/leader.FTR2.15062010.14 http://leader.pubs.asha.org/article.aspx?articleid=2291889&resultClick=1

- Coyle, J.L. (2014, April). When the cause of dysphagia is not obvious: Sorting through treasure and surprises in the medical record. Session presented at ASHA Health Care & Business Institute, Las Vegas, NV.

- Langmore, S.E. et al. (1998).

- Langmore, S.E. et al. (1998).

- Taylor, J.K., Fleming, G.B., Singanayagam, A., Hill, A.T. & Chalmers, J.D. (2013).

- Coyle, J.L. & Matthews, C. (2010).

- Strachan & Solomita. (2007). Aspiration syndromes: Pneumonia and pneumonitis – preventive measures are still the best strategy. The Journal of Respiratory Diseases, 28 (9), 370.